The Friends of Aşıklı Höyük Association carries out various support activities in order to protect the cultural heritage of Aşıklı Höyük and its environs, especially to raise awareness with local people to adopt and protect this heritage. In this context, they applied for the following program: “Grant Scheme for Common Cultural Heritage: Preservation and Dialogue between Turkey and the EU-II (CCH_II)”, which the European Union opened in 2020. His project was successful. This interdisciplinary project, planned together with partners at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and University of Dundee (UD), brings together art, history, art history, archeology and anthropology, and is one of the first settlements in the world to bring together agriculture, architectural elements, and the mind. It aims to introduce Aşıklı Höyük, which developed many firsts, such as surgery, socio-economic dynamics and communal life. One of the most important of the project activities, where the works of 13 artists from Turkey, England, Spain, USA and Colombia will be presented in different art forms, is the exhibition, “Traces of the Excavation: From Archeology to Art, From Art to Archeology”, which plans to open in Istanbul in February-March 2022. Curator and writer Gary Sangster was invited to assist Turkish curator Fırat Arapoğlu to support the development and presentation of the exhibition as it is an international project. Sangster summarised his aim as developing a fruitful dialogue between archaeologists and artists. We had a conversation with Gary Sangster who had diverse experiences as a curator.

It is interesting that you have a curatorial writing career on different continents like Australia, America and also Europe, England too. How has this multi-land geography shaped your notion of art? And your notion of curating a show?

There are two questions here. To consider transnational cultural work and lived experience as they affect my idea of art and as they affect my strategies in curating exhibitions in concert with my overall curatorial project.

From my perspective, it is impossible to comprehend the scope and power of the colonial and post-colonial world from a single national vantage point without being bound by the regime of the marginal and the dominance of the local. To better understand globalism and its impact on art, it is productive to engage in different fields of art and work with artists and audiences from different communities and cultures. A better understanding of the nature of difference, across cultures, communities, races and genders will make the translation of knowledge, rituals, and protocols more feasible, at least. A lack of shared knowledge and agreed histories, along with dis-equity of resources are some of the critical barriers to constructive dialogue through art.

The term ‘art’ is itself too generic as a descriptor because it can be applied to so many different forms and practices. I think it useful to parse the concept into different fields that can be analysed on their own terms and within their specific hierarchies. One way to undertake this parsing is to consider art as a suite of different economies where support and processes are earmarked and secured for specific kinds of art. These discrete economies operate somewhat independently with rare overlaps, but it also means they function more laterally, and have the capacity or even the incentive to transcend nationalism and the specific constraints of place, and can be stretched globally – so we might consider, for example, the craft economy, the design economy, the biennale economy, the education economy, the auction economy, the museum economy, the public art economy, the site-specific installation economy, the internet economy, the NFT economy, and many more. These different forms of artistic practice operate discretely and have their own specific set of protocols and practices and sources of capital that define their boundaries and limit transmission across different economies.

Curating exhibitions is not rocket science, but there is a checklist of concerns that should be considered. The key elements of the exhibition experience are spatial, temporal, and luminal (perhaps not a word). But within the inherent visuality of exhibitions, space, time, and light considerations are the primary operators to be explored and experimented with. We move through a constructed or existing site, over a specific or flexible time period, and recognise imagery and objects and the interconnected relationships between them through the effects of light.

But before we get to that exhibition installation phase, we have the discursive process to consider – the artworks as artefacts, the weight and effect of the history of art, the site of their production and the cultural history of that place of production, as well as the site of their presentation and the nature of the prospective and intended audience/s. The discursive process in exhibitions is dominated by juxtaposition and arrangement, the self-conscious interaction of works in specific spaces to construct a somewhat linear relational narrative; to tell a compelling story, about art or about other imagistic or object-based content and meanings.

Felix Gonzales-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm)

Many people seem to think that art is somewhat universal and can reach everyone. My experience is that this fiction produces many misunderstandings about the specificity of art, its relevance and resonance to a particular time and place. It is important to be conscious of the fact that not every artwork and not every art exhibition can reach anyone and everyone. Like any product (which art and exhibitions are, albeit more value-laden than other more commercial or functional products) there are specific market segments to be considered. Curators must ask ourselves, who is the exhibition designed for and why, and how will it connect with or engage them, and then what effect will it potentially have on the audience/viewer. This last point is why self-censorship is so prevalent in museum exhibitions, it clearly is not ‘anything goes’.

When we faced the reality during Harald Szeeman’s exhibition, after his death, at the Prada Foundation, bodyguards constantly warned, “Don’t touch the art work”. We were kind of disappointed. How can we sustain the discourse before the artworks or vice versa?

The regulatory surveillance of the exhibition space, invigilation, is indeed a structural impediment to audience engagement with new art, but it is also a pragmatic response to the burgeoning popularity of contemporary art.

This is a product of two things, first, most obviously is the inherent fragility of material culture, and second, a somewhat more distorting effect of contemporary Western regimes of originality and authenticity, where preservation of artefacts in their original form, innately connected to the hand of the maker, and therefore sanctified in its uniqueness are the dominant modes of aesthetic evaluation.

This is also part of the public/private dilemma in the experience of artwork. Public space, exhibition space has different protocols in relation to private space. The protections, or lack thereof, are different and so the experience is different as well. Private space is also a privileged, high value experience.

We have come to accept that the debilitating effects of this distancing between the artwork and viewer is a trade-off, for coming into fairly close contact with something precious/rare/unique, significant, and informative. This deliberately constructed fissure between the artwork and the audience, is now an elemental component of the discourse of engagement. Due to the potential risks of damage, alteration, or ordinary wear and tear, exhibited artefacts/artworks may now only be observed at a distance, surrounded, encased, or enclosed in protective armature, effectively separating the audience from the work. It is a curatorial/museological condition of contemporary exhibition experience. We accept it and work with it. We factor it into our experience and understanding of work.

The reality is that this framing: the white cube, the protective armature, the glass case, the invigilation, has become as seamlessly enmeshed with the experience of the work itself, as a gold-leaf frame protecting a Renaissance painting .

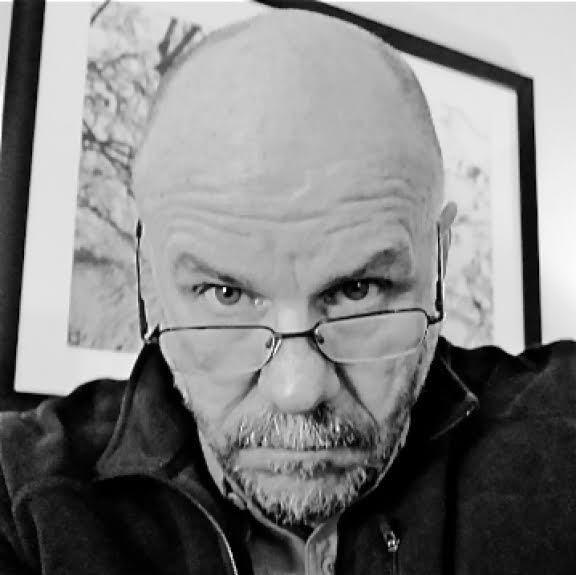

Gary Sangster

If you could choose a decade from the decades you have lived through art history, for example the 1970s… What can you tell us? What was right, wrong? Is it fair to judge today’s art in terms of those days that were full of liberty but poor in money?

I think it is not that useful to think in terms of decades, as a shorthand device. I would like to look at things from a somewhat broader perspective, seeking to understand the critical fissures that changed art and culture. What has happened to art in the entire post-war period? The great flourish of post-war Abstract Expressionism was in a sense a continuation of the aesthetics of more traditional painting, on a somewhat grand scale. While this form continues to accrue willing adherents, it has, in reality, been in a cultural and critical eddy for many decades. I would suggest It was radically eclipsed by the bifurcation between spirituality and materiality represented in the work of Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol respectively.

This post-second world war dominating USA/European dialectic has created a fertile ground for the exploration of a broader and more expansive set of artistic forms and aesthetic systems. The veritable explosion of different genres of art and different kinds of artistic production emerges from this critical material/spiritual framework.

There is so much staggeringly great art that can be described and discussed since the 70s. I would mention just two here. I have been astonished by the compelling work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose extensive photographic project work sought to reclaim the right and responsibility to represent a German culture that had been nearly annihilated by Nazism, by photographing industrial towers. Their work poses the most basic of questions: in the de-humanised period of the post-Holocaust era, how does one make art again?

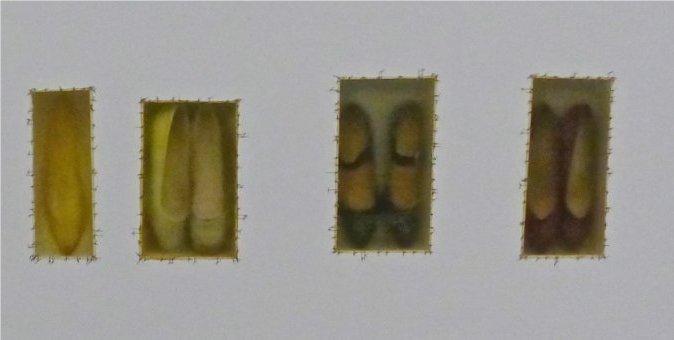

I would also propose a profoundly moving memorial work by, which incorporates shoes of the disappeared from Colombia, set into shoebox size crypts in the wall.

Both of these sets of works have a mesmerising quality that incorporates both political potency and remarkable visuality, yet with a deeply affecting subtlety and nuance that never collapses into what could described as ‘torture porn’.

There is a complete library of great artwork that could be discussed, that has emerged from this tension between the material and the spiritual in art.

I think what has been developing for the past three or more decades is an extraordinary redefinition of cultural globalism, where the East and the third and second world is joining the West and first world in an extensive re-evaluation of site, form, and presentations of content and material such as power, capital, race, gender, environmental fragility, species extinction, etc. This has been accelerated by hyper-expansion of affordable technologies that transmit information and can produce experimental forms relative inexpensively and accessibly, for both the maker, the producer/museum and the viewer/audience.

Doris Salcedo, Atrabiliarios, 2004.

What is the big crisis in art now and then?

A crisis generally is a known thing, a visible emergency, a quantifiable state. I think one of the key crises we have in art currently is somewhat muffled or hidden from view, through its sheer ubiquity. I would suggest that the deluge of high-quality imagery, the inflation of sensuous visuality we experience on a daily basis, diffuses and devalues the potential for art and artists to be genuinely impactful.

This surfeit of images promotes an attention-seeking, celebrity cultural-economy of ‘likes’ which is a form of currency that may camouflage where more significant cultural work is being undertaken and where ground-breaking art is being produced. I think this leads to another crisis where art and artists are pursuing relevance through instrumental strategies, producing recognisably socially responsible artwork. Conscientious work which has inherent value in the moment, being relevant to communities, but is not necessarily significant to the future of art and culture.

I would suggest that the most important art creates new space for new forms of cultural experience. One crisis for museums now is how the rapid shifts of form and media interrupt their reflective deliberations of discursive value and becomes a statistical and quantifiable process of identifying consensus. A kind of algorithm of automated critical cultural success is in the ascendence here, hence the somewhat repetitive global exhibitions, biennales, and art fairs that are self-reinforcing of the current idiom of high-value artefacts. This is not to say that many of these artworks and exhibition projects are not critically significant, it simply means that a diversity of form and meaning in art, its experimental potential, is somewhat diminished or even suppressed, and a churning homogenous internationalism is the new aspirational genre.

What is contemporary art to you? How can you define it?

In a technical sense contemporary art is art made by living artists, usually in a specific time period, say the last 25 years. While we may not want to define contemporary art, we can be comfortable describing it or identifying it. Art really is an institution that can only credibly exist when held in the matrix of near-universal consensus. Both modern art and contemporary art took a long time to gain the necessary consensus; and many people still have doubts about the aesthetic value of Duchamp’s urinal or Warhol’s soup can imagery, even now.

Richard Long, Connemera Scuplture, Irland, 1971.

Contemporary art can and indeed will be anything that has gained identifiable consensus in that cultural arena, so a line or circle of rocks by Richard Long or a string of electric lights by Felix Gonzales Torres, are artworks, very fine examples of contemporary art, because we can generally agree they are.

We should understand though that acceptance of and consensus about art will differ across communities, cultures, and classes. It’s not that anything can be art, it’s that in the field of contemporary art there is a narrow range of what could be described as ‘relevant consensus’ that sifts and dissects cultural production to determine what is of most value to the field. How that evaluation is done is complex and driven by both art theory and art practice. Artists, curators, writers, gallerists, collectors, educators, and theorists are all involved.

For me, the role of art theory in the construction of art is critical. Everyone has a theory of art, which is culturally constructed and embedded in our cognitive experience; we sometimes call it ‘taste’. Without this theory each of us possesses, we would not be able to recognise art for what it is, art. Art is art, not because of its prepossessing qualities, art is art and is relative in value according to our innate theory.

But we should also understand that art theory is very conservative in operation, surveying and describing the past exclusively. Art theory is not really theory at all, as it contains no hypothesis and has no predictive function, it cannot tell us what art will be like in the future. It can contribute to, but it cannot construct or define, the consensus necessary to produce art in new forms.

Lets go back to the site where we met actually, at Aşıklı Köyü Kazısı where the inhabitants lived 10 000 years ago. What is so interesting to me is that there is no sign of an image. We know where these so-called Neolithic humans slept, ate and whom they fed and and buried but we don’t know how they expressed themselves. There are no carvings, drawings or animal reliefs.

First, I want to ask you what is it that we project to them?

An archaeologist would have a richer and deeper understanding of what we, today, project onto the people who originally inhabited the Aşikli Höyük site. Archaeologists are retrieving and interpreting the material culture they uncover with an expert, scholarly sense of prehistory. They are also analysing their material discoveries by bringing to bear emerging technologies to better understand the chemistries, genetics, and biologies of more elements from the ancient record.

From my perspective as a contemporary art curator and art historian, my projections are more coded, more constrained by my introductory knowledge of the recent research of archaeology. Perhaps understandably, my projection leans towards identification with ancient people, their humanity, or rather their humanness in a psycho-physiological sense, rather than a cultural, value-laden sense. I project a sense of their consciousness and cognitive and corporeal learning capacities, the kinds of capacities that enable humans to sustain more social and cultural complexity than genetically-coded instinctual and species-defined behaviours, that may be evident in non-human life.

The fact that no signifying practices have been preserved in the archaeological record at Aşıklı Höyük is unusual, but we should not assume that form and representation did not exist even though it has not been found there as a material artefact or image. While the evidentiary record cannot tell us what these practices were, I prefer to assume they existed. Due to our contemporary bias towards signification practices we project elaboration, decoration, and production value onto pre-historic communities engaged in the making and preservation of artefacts, and we avidly search for this evidence. These preserved and protected, elevated perhaps, cultural traces demonstrate consciousness and provide us with insight into social development. But at Aşıklı Höyük, without artefacts at hand, perhaps their signifying practices were entirely temporary or performative, like the flat-clasped hand gesture for prayer, the raised fist for defiance, a simple turning to face the sun in the morning, or a small group forming a circle around a tree. As Mihriban Özbaşaran, the chief archaeologist at Aşıklı Höyük has said, there are many things about the site which are unknown.

And, what is contemporary about them, aren’t they always the seers?

The ‘contemporary’, that is, our current context, where and how we live now, and what we know and have access to and can interpret, creates a dominant regime of seeing and filters how we read the past. It is not that we are incapable of imagining other forms of experience, it is more that in trying to understand ourselves through a deep knowledge of the past, we tend to drift into the pursuit of what may or may not be universal, or how we can define and understand what it means to be human, frequently forgetting what a dominant factor our lived experience is when trying to look outside it. I am very fond of John Berger’s insight from his novel ‘G’, which is a direct quote from R.G Collingwood’s “The Idea of History”: All history is contemporary history: not in the ordinary sense of the word, where contemporary history means the history of the comparatively recent past, but in the strict sense: the consciousness of one’s own activity as one actually performs it. History is thus the self-knowledge of the living mind. For even when the events which the historian studies are events that happened in the distant past, the condition of their being historically known is that they should vibrate in the historian’s mind.

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Framework houses in Siegens.

What will be your curatorial approach in this project?

Let me be clear that this is not a curatorially-driven project. It should not be viewed as curatorial conception and production. It is a research project that has had an extended evolution and has involved a range of shifts and developments over several years.

As it is an international project, I was invited to assist Fırat Arapoğlu, a Turkish curator, to support the development and presentation of the exhibition. The entire project including the touring exhibition is generously supported by the European Union and implemented by The Friends of Aşıklı Society, The University of Dundee, and The Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The curators’ task is to curate an exhibition that emerges from the trans-disciplinary engagement of contemporary artists with archaeologists and the Aşıklı Höyük site. Consequently, the curatorial function is one element in the development of a productive dialogue amongst the archaeologists and artists.

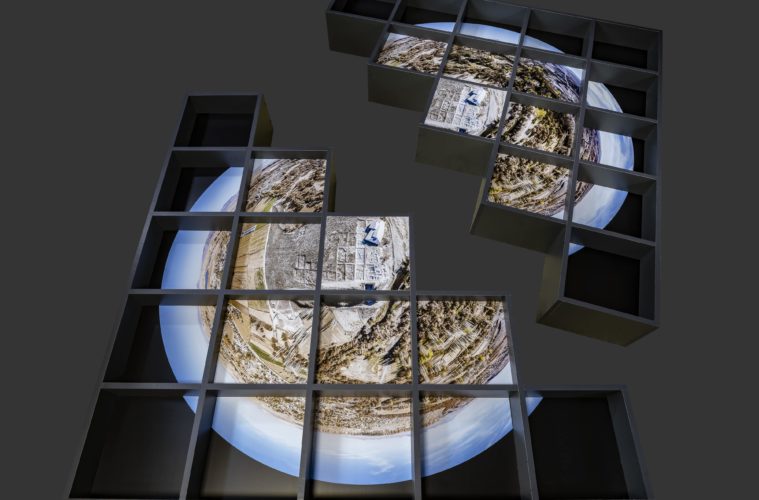

As the project has evolved, it was envisaged that the artists’ work for Lines of Site / Kazı İzleri should be informed and developed by their ongoing interaction with the unique archaeological qualities of the Aşıklı Höyük site. Their intellectual and artistic inquiries to be represented through making new work and developing new forms, images, and ways of using space and light as creative reflection of their insights. The artists international range of perspectives, coupled with their use of different media and their unique research concerns, will generate a diverse range of themes that both reveal and document the site in powerful new ways and resonate with a broad range of audiences.

Critical elements driving the artists new work all emerge from the Aşıklı Höyük site including the compelling and evocative quality of the experience of this site and its structures for shelter and dwelling; the inherent materiality of ancient building materials, forms, and layouts; the universal qualities of humanity embedded in the development of communal environments that lead to settlements, villages and townships; or the role of artists or archaeologists in preserving and interpreting the material archive.

The Lines of Site / Kazı İzleri exhibition includes thirteen artists from Catalonia, Colombia, the UK, and Turkey and curators from Australia/UK and Turkey. Artists: Özgül Arslan (Turkey/UK), Eva Bosch (Catalonia/UK), Şahin Domin (Turkey), Ahmet Rüstem Ekici (Turkey), Leyla Emadi (Turkey), Stephen Farthing (UK/US), Murat Germen (Turkey), Osman Nuri İyem (Turkey), Blanca Moreno (Colombia), Dillwyn Smith (UK), Hakan Sorar (Turkey), Anita Taylor (UK), Emre Zeytinoglu (Turkey) and Curators: Firat Arapoglu (Turkey) and Gary Sangster (Australia/UK).

The exhibition tour is scheduled for Istanbul, Dundee, and Barcelona and it will be initially presented at the historic Hüsrev Kethüda Hamamı in Istanbul from Jan 31–Feb 28, 2022. It will then be exhibited in Dundee and following that in Barcelona.

What we have learned from the process so far is something we already inherently understand; that the critical methodologies of the two disciplines, archaeology, and art, are fundamentally different. Yet they consistently deal with remarkably overlapping sets of concerns: visuality, materiality, spatiality, time, the nature of the archive, meaning, value, and what it means to be human, and how that humanity is expressed and codified through the production and retention of the artefact.

The value of linking these two distinct fields in a single project offers the opportunity to realise a more extended set of outcomes, outcomes that may be enhanced, nuanced, unusual, or unexpected. Engaging in this dialogue posits the opportunity to rethink established protocols, strategies, and approaches to one’s field, not to disrupt it or even query it, but to amplify it, to offer the possibility of new lines of inquiry from a different perspective.

In the context of this project, the research and deep thinking the Aşıklı Höyük archaeologists have applied to their work at this site becomes a platform for the artists to undertake their experimental and imaginative inquires and to generate forms that are inflected by the site, the materiality and form of the topography, the ancient civic contexts, the recovered materials and artefacts and their inferred uses, as well as the understanding of the original inhabitants’ lifestyles.

The intentions of this project then are deceptively simple, to provide time and space for artists to engage critically with a significant archaeological site, to enter a dialogue with the archaeologist responsible for uncovering and interpreting the finds from the site, and to produce an exhibition that articulates some aspects of their understanding and reactions to the site. Through this interdisciplinary undertaking, the archaeologists hope to gain additional insight into the visual and material forms of the site through the lens of contemporary visual artists and their imaginative and creative practices.

Many artists tend to be curious and eclectic, drawing on sources and insights that don’t necessarily traditionally align and inform one another. In adopting an expansive critical method and grounding their work, their research in materials and practices that are inherently visual, yet spill over into other visceral, spatial, and temporal sensibilities, they seek to engage, understand, interpret, represent, and communicate. Archaeologists, no less curious, are constrained by the evidentiary demands of their field. And both artists and archaeologists are deeply invested in the construction and definition of meaning and value of material artefacts.

What is striking, but perhaps not too surprising, about the artists’ discussions so far is how very different their approach and their work will be. Beginning at the same point but exploring the different dimensions of the archaeology of the site, filtering their research and information through their media and technique to develop new work to posit new ideas and express new forms that emerge directly or tangentially from their engagement with Aşıklı Höyük.

The imaginative and open-ended nature of the artists’ project permits an expansiveness of thinking and experimental methodology, a project that the archaeologists are willing to engage and explore to enhance and expand their own systems of research and accumulation of knowledge drawn from the discoveries at Aşıklı Höyük, which suggests that an ongoing dialogue will be mutually beneficial to the production of knowledge embedded and yet to be discovered and interpreted from this site.

How do you design a museum or an institution’s programme? What are your starting points and also breaking points?

Museum work for me is always contextual. It is essential to ask the same critical questions when developing an exhibition or developing a programme. What is this institution, where is its place, what is its history, who is the audience, what are their values, what would they like to experience, what would they learn through that experience? A programme should balance many competing issues to create a dynamic suite of experiences that resonate with the audience, that are relevant to them. Otherwise, they won’t be interested in the work or the idea.

Exhibitions generate new experiences, tell stories, represent experience and cultures and people. Exhibitions need to speak to their audience. Because of the historic regime of easel painting, visuality is the dominant sensibility of museums. However, and this is especially true for contemporary art, exhibitions are structured in space and through time, and provide sensual and visceral visual, tactile, and aural experiences. So, Biennale culture, for example, can be much more akin to the carnival than the museum, where the thrill and excitement of the unknown and the magical are in the foreground. The visceral impact of excitement in exploring the unknown posited through biennales versus the refined encounter with the reflective space of the museum.

Have your main challenges changed over time? Are there any permanent ones?

The main challenge remains to ‘know your audience’. This is more difficult now, as values and meaning shift and change so much more quickly because the flood of information and ubiquity of technological facilities. The lag time between information cycles is so compressed, that it compresses the space for reflection and constructs rapid change across all communities. And those changes are not necessarily in sync.

Attention-seeking and trending are the dominant markers of a shallow culture, while museums have historically been striving for deep engagement. We are now living in a distributive culture that accrues and discards forms and styles and artefacts at a rapid clip, as opposed to an acquisitive culture that collects, protects, and interprets material culture for future learning. These are paradigm inflections, which may in fact be the precursors to more extensive paradigm shifts in the way culture is understood and experienced. In response, museums must become adept at operating in both registers, preserving the initial frameworks and artefacts of current culture and interpreting and articulating the meaning of that material for future audiences, which is the traditional purpose of museums. In a sense museums are tasked with sifting and rehabilitating the discarded refuse of a contemporary culture voraciously consuming and excreting all manner of form and content.

This is difficult and expensive work. Material culture is notoriously fragile, and the volume of artwork being produced currently exceeds the capacity of existing museums to function in a comprehensive manner. Critical cultural decisions and investments must be made on a deadline, in a compressed timeframe, inflected strongly by the source of the most abundant resources. In other words, the nature of cultural value can be easily distorted by the influx of new, somewhat self-regarding capital. But this not necessarily an unusual condition, if we consider the history of patronage as one of the controlling frameworks of the development of collections and museums – the Pharaohs and the Medici, made most of the aesthetic decisions about art production and collections. It is just that the current pace of change and the rapid influx of capital afford little time for considered decision-making and consensus building. The risk of bad decision-making about art and exhibitions through flawed rapid-fire processes is potentially greater than we imagine or fully understand. Although a careful examination of some of the outcomes can provide a fair indication of some ill-considered decision-making in the realm of contemporary curatorial practice and museum collection practices and exhibition production.

Do you think it still matters and it will always matter where you are from in contemporary art?

It is not so much that it matters where you are from or that it is a critical factor in your approach to or response to art, but it is a condition, and something that in a sense is unalterable, like the time of your birth, the place of your birth and the place of your acculturation and education, these condition you as developmental phases and continue to resonate with you.

Place is a condition of identity; it is the culture, the history, the economy, the politics of place that provide the framework of your emergent and evolving identity. How you use that knowledge and refine it affects what you can do and do in the world of cultural production and reception.